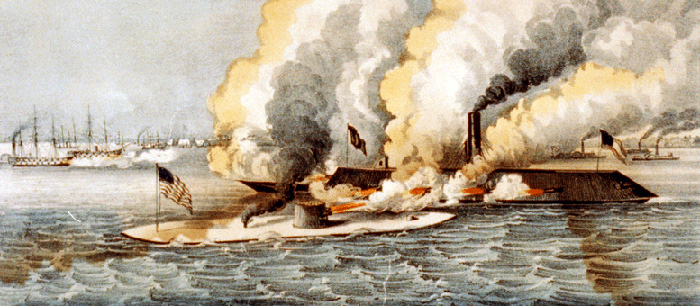

At the estuary of Virginia’s James River with the Atlantic Ocean, a waterway known as Hampton Roads, history turned on March 8-9th, 1862. The navy of the United States of America was participating in a progressively successful blockade of the breakaway Confederate States of America, designed to strangulate the economy of the natural resource poor, industrially underdeveloped southern states and force an environment of surrender. Warships of the U.S. Navy, the USS Cumberland and the USS Congress were positioned to shut down the critical Hampton Roads waterway and prevent maritime resupply of the confederate capital at Richmond while facilitating the impending Peninsula campaign of Union forces directed by General George McClellan. The two great ships were positioned in blockade to take on any challengers when on the evening of the eighth an entirely new threat presented itself. The wooden battleship USS Cumberland found itself under attack by strange sail-less craft with angled sides upon which its canon shell harmlessly bounced off and in a technique worthy of ancient Greek battles, rammed by her and sunk. The strange craft turned its sites on the USS Congress, who found itself equally helpless against the impervious craft and determined instead to dash itself against the shoals to prevent sinking. This made the Congress an immobile object for target practice by the alien craft and it was pummeled into surrender. In a relatively brief battle, a single craft had taken down two American warships, caused the deaths the deaths of 241 naval seamen in the greatest loss of life to the American Navy until 1941’s Pearl Harbor, and put the entire strategy of blockade to victory in peril. This unique threat was the CSS Virginia, the redesigned ironclad warship reconstituted on the shell of the previously captured USS Merrimac. In a brief battle, the south had found its magic bullet that could re-orient the entire world of military strategy. For centuries, the concept of naval battle was unchanged – the goal was to attain close quarters with the opponent craft and turn your armaments upon it, achieving destruction of the craft, or at least sufficiently damage it to prevent its further utility as a sailing vessel. The logic of several thousand years of armed combat at sea ended in one fell swoop on March 8th, 1862, when a vessel impervious to canon and whose mobility was driven by power under the water line rather than sail presented in the reality of the CSS Virginia.

poor, industrially underdeveloped southern states and force an environment of surrender. Warships of the U.S. Navy, the USS Cumberland and the USS Congress were positioned to shut down the critical Hampton Roads waterway and prevent maritime resupply of the confederate capital at Richmond while facilitating the impending Peninsula campaign of Union forces directed by General George McClellan. The two great ships were positioned in blockade to take on any challengers when on the evening of the eighth an entirely new threat presented itself. The wooden battleship USS Cumberland found itself under attack by strange sail-less craft with angled sides upon which its canon shell harmlessly bounced off and in a technique worthy of ancient Greek battles, rammed by her and sunk. The strange craft turned its sites on the USS Congress, who found itself equally helpless against the impervious craft and determined instead to dash itself against the shoals to prevent sinking. This made the Congress an immobile object for target practice by the alien craft and it was pummeled into surrender. In a relatively brief battle, a single craft had taken down two American warships, caused the deaths the deaths of 241 naval seamen in the greatest loss of life to the American Navy until 1941’s Pearl Harbor, and put the entire strategy of blockade to victory in peril. This unique threat was the CSS Virginia, the redesigned ironclad warship reconstituted on the shell of the previously captured USS Merrimac. In a brief battle, the south had found its magic bullet that could re-orient the entire world of military strategy. For centuries, the concept of naval battle was unchanged – the goal was to attain close quarters with the opponent craft and turn your armaments upon it, achieving destruction of the craft, or at least sufficiently damage it to prevent its further utility as a sailing vessel. The logic of several thousand years of armed combat at sea ended in one fell swoop on March 8th, 1862, when a vessel impervious to canon and whose mobility was driven by power under the water line rather than sail presented in the reality of the CSS Virginia.

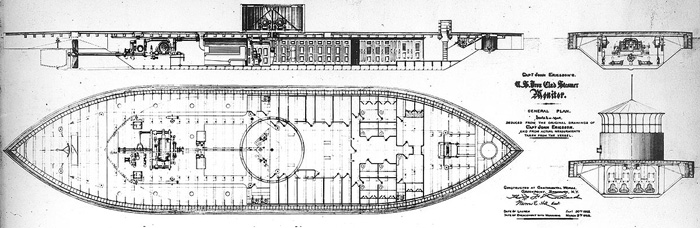

Unknown, however to the Virginia, on the same night of March 8th, an even more revolutionary craft had entered Hampton Roads from the ocean, and was positioned on March 9th to take on the indestructible Virginia. She was the USS Monitor, and she was not just a revolution in armour and propulsion like the Virginia, but additionally, a revolution in armament. The Monitor was the culmination of the revolutionary engineering ideas of Swedish immigrant engineer John Ericsson and the enormous resources of the north applied to technology. The south’s engineering was creative and facile, but limited to the available resources, and putting the Virginia with her iron plates together was a major stress. To obtain enough iron for armour plating many railroad track tailings had to be sacrificed, and the south was not in a position to create a fleet of such vessels. The Virginia was placed on the platform of a previous wooden ship, and her plating placed to the water line. As she fired off ordinance, she became necessarily lighter in the water and began to draft less, exposing her wooden underframe. The Monitor was something else entirely.

Ericsson designed her as a new type of vessel, providing almost no available target with the craft designed to float as a craft even along the waterline, and for the first time, with armaments impervious to the craft’s position in the water as they were placed in an armoured rotating turret that could rotate to any necessary firing position. Ericsson had undergone the struggle of all immigrants, having his evocative ideas dismissed by so called experienced naval personnel who felt they would never work, and who had his reputation injured in a previous disastrous trial years earlier when a previous demonstration in 1844 in the presence of President Tyler of an early turret had exploded, killing 8, and making Ericsson a pariah. Ericsson, who had the design of the rotating turret pilfered rather than designed by him, never gave up the idea. When spies suggested the development by the south of the Virginia, interest returned to Ericsson’s idea, and President Lincoln, who had a love of new technology, approved the very expensive building of the Monitor.

On March 9th, the CSS Virginia came out to play and found itself blocked by a craft even more distorted than itself. Ramming the craft proved unfeasible as the monitor’s underwater screw design powered by steam and raft design proved too nimble. Additionally the Monitor’s available outline for canon fire was its rotating turret alone, made of impregniblehigh grade steel to the Virginia’s explosive, non-penetrating shells. The battle proved inconclusive; but the lesson was clear. The Virginia, now raised in the water, was becoming vulnerable, and its tactics would have no effect. The battle was ended with the ships removing themselves from close contact, but revolutionary first battle between two ironclads at sea changed naval warfare forever.

The amazing Monitor design put forth by Ericsson had over 40 patentable designs and navies across the world took notice. Steam powered screw propulsion, rotating, repeat firing armament turrets, reduced available target design, comprehensive rivet armour plating – Ericsson’s little Monitor was inspration for what would become the massive Dreadnought class battleships of the 20th century and would change forever battle tactics. The Virginia, as spectacular as was its brief success, was made impotent by a superior craft, and as the south was incapable of creating numerous ironclads as could the north, became an expendible structure scuttled by its own crew later that year. The blockade held and grew in intensity and eventually the south was strangulated from the vise from without and the lacerations within.

Hampton Roads, Virgina is now the site of the one the great naval bases in the world in Norfolk, Virginia, and one can look at the docks and see the various permutations of John Ericsson’s breakthrough thinking as far as the eye can see. Once again, the experiment that is America, the freedom of immigrants to prove themselves in the free expression of ideas, came to fruition in the narrow waters of Virginia in 1862, where it had done so many times before.

(further study of this event and other stories of the American Civil War are available online on the terrific site http://www.civilwar.org/)