Sunday morning one awoke to the terrible news that Bart Starr had died. Terrible, in that the sense of foreboding of the announcement has lain like a fog over the last several years as the once indomitable individual had been struck with health insult after health insult, leaving the inevitable seemingly possible with each passing day. First stroke, then another stroke , then heart attack, then seizures assaulted this once great athlete, leaving him a whisper of his former self and fragile to the the clock running out without a redemption story. And yet, as one who grew up with the legend of a champion unbowed by any challenge, Starr turned his competitive fire onto his health crisis like the final drive in the fourth quarter, and sought victory against the tremendous odds. At one point unable to speak or walk, Starr, through tortuous therapy, stem cell injections and indomitable will managed to rouse himself on a cold rainy night to attend Brett Farve’s Green Bay induction into the ring of immortality during his number retirement in November, 2015 creating one of the great emotional passing of the torch moments in sports history.

It was Brett Farve’s night, but the crowd responded to the presence of the frail Starr with a heightened roar that let all know the emotional core of ultimate greatness for all who were present resided in the unique personhood of one Bart Starr. Greatness in sports translates for most into greatness in life – the ability to maximize one’s available capacities thrown against severe challenge to not only compete, but surmount and ultimately conquer. Few conquered life and provided such an exemplary example for others to emulate as did Bryan Bartlett Starr, and in celebration of his life, resounds proudly as Rampart’s People We Should Know – #34.

“He’s got to have the respect of his teammates, his authority must be unquestioned, and his teammates must be willing to go through the gates of hell with him ”

Bart Starr on what defines a great Quarterback

There was nothing to suggest the rookie drafted by Green Bay in 1956 in the 17th round from the University of Alabama was such a quarterback. A quiet, to some overly polite, physically unimpressive young man was almost invisible to the other players on the Packers, who assumed he would be another one of those players who drifted in, and out, of the NFL without tracing any memory on those who played with him, or those who watched. He was the fourth of four quarterbacks available to the new coach in 1959, Vince Lombardi, hired to somehow shake the Packer franchise out of the losing doldrums that had seized the once great franchise and threatened its very survival. Coach Lombardi was earthshaking in his approach, unforgiving of casual effort, careless mistake, and to some brutal in his drive to seek perfection. For many veterans, Lombardi was a intolerant taskmaster. To Starr, he was like an epiphany. Frankly, Lombardi reminded Starr of his unbending, difficult to please military father, and Starr understood how to deal with stern discipline better than most. Interestingly, Lombardi saw in Starr what others did not see, a field general that would be capable of translating Lombardi’s vision onto the field of play, and be his perfect reflection. Soon, other players noted that Starr was tireless in his study, repetition, and discipline, and although Lombardi was harsh and unyielding to others, he rarely raised his voice to Starr.

The results of their combined contribution was almost immediate, and progressively spectacular. Within a season, the heretofore placid Packers were the irresistible force of the league, getting to the championship game in 1960, winning the NFL title in 1961, and crushing all before them in 1962. Among the many star players, the duet between the coach and his field reflection the quarterback was the premier example of excellence in all of sports. The team was anything but boring, with philanderers, gamblers, carousers, and warriors, but on Sundays the nation was captivated by a team that had made perfect execution its goal, and more often than not, carried it out to perfection. At the center of the maelstrom was the quiet leader who said yes, sir , no, sir to his coach, was not heard to swear, didn’t smoke, and went home to his wife and family. Starr went to church, always had time for anyone who wanted a moment or an autograph, and was a leader in charity and community. Starr was what the mythic example of the perfect leader so treasured by Americans but rarely seen in real life – humble, deferential, and at moments of stress and crisis, inspirational. Amazingly, what you thought you saw, was absolutely what you got.

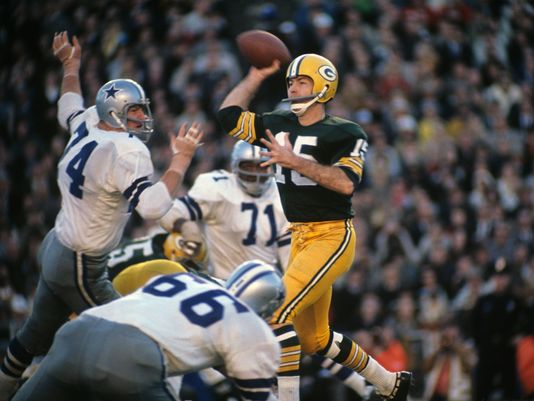

Starr was not just a great leader of men; he could play. In a time when running the ball was king, and passing was an afterthought, Starr was a four time All Pro, the era’s most accurate passer, and a devastating play caller who befuddled defenses with unpredictable downfield gambles and led the league in yards gained per completion. The team responded to his call for total on field authority, and followed him through the gates of hell to 5 NFL championships in 7 years, including three in a row. He was the MVP and winning quarterback of the first two Super Bowls. He was absolute steel in stressful moments, playing a position that in the 1960s held none of the physical contact protections slathered on quarterbacks today. The image of Starr in the picture above, a single thin bar between his face and the surrounding violence was emblematic of the physical abuse the quarterback was expected to endure.

“Coach, the linemen can get their footing for the Wedge, but the backs are slipping. I’m right there, I can just shuffle my feet and lunge in.” Lombardi told Starr, “Run it, and let’s get the hell out of here!”

Sideline conversation during final timeout between Starr and Lombardi, December 31,1967 – the ‘Ice Bowl’ NFL championship game Green Bay vs Dallas

Nothing defines Bart Starr or the mythic status of the Green Bay Packers as does the final drive of the so called “Ice Bowl” of December 31, 1967, in the NFL championship game between the aging Packers and the upcoming Dallas Cowboys, in possibly the most appalling conditions for an extended sporting event defined by violent contact. The field temperature at game time was an all time frigid -13 degrees F, wind chills -50 degrees, and the conditions deteriorated from there. The playing of the game under such conditions was epic in its ludicrous expectation by the league for athletes to actually perform in such a dangerous and unyielding environment, much less the 56000 bundled eskimos masquerading as attending football fans. What was even more ludicrous was how well they performed. The so called warm weather team, the Cowboys, improbably outplayed the Packers after falling behind 14 to 0 early, a deficit that would have eliminated almost any other team, but with 4:30 to go in the 4th quarter, the Cowboys had dominated the second half, and the Packers were left on their 32 yard line, down 17 to 14. The Packers had been pummeled by the Cowboy defense in the second half, and recognized this was likely their last chance. The field was an ice rink, the players beyond weak with frostbite, and a field goal in such conditions to tie, an abomination to the kicker’s foot. The story of the final drive huddle was as epic as the situation – players said afterward Starr entered the huddle, looked in their eyes, and stated the time was now, and they were going to score.

And so the The Drive began, with Starr positioning short passes to receivers with treacherous footing, and catching the Cowboys off guard with miss direction runs. With less than a minute to play, Starr had brought them down within a yard of the goal line, and like the champions they had always been, they could smell the win. The treachery of the field, however, awful in other places, was beyond comprehension near the south end zone of Lambeau Field. On two consecutive running plays, the running backs slipped and fell, barely returning to the line of scrimmage. With 16 seconds left, Starr called his final timeout, came to the sideline , and had the above conversation with Lombardi. Lombardi admitted after the game, he was so cold, he was not sure what play Starr stated he would run, but they both knew the years of preparation had led them to seek victory and not play for a tie, magnified by the desperate field conditions.

With no timeouts, the Cowboys assumed a roll out pass, and Starr in the huddle called another running play. He told no one that it was his intention to live or die on his own, and took the ball over the guard in the most famous play in the most famous game in NFL history.

It was the triumph of a career of triumphs, made special by the recognition that people performing under such conditions elevates our understanding of what is human capacity to other-worldly levels.

Bart Starr went on to other triumphs, but nothing cemented the vision of his unique triumphant stature like his determination to take the solitary plunge across the line in the twilight of an arctic wasteland. He could do no wrong after that play, and further lived up to his impossible standards off the field as well as on.

No one who met him ever left him feeling untouched by his deep humility and humanity. He was the superhero who acted like the everyday man, and his later foibles as a coach unable to explain to younger players how to function at the olympian levels he had functioned at, left no mark on his greatness. I recall in grade school, my teacher asked of the class who they wanted to most be like when they grew up, and when the hands went up, Bart Starr gave Jesus Christ a predictable beat down. People wanted to be seen with him, charities could always count on him, and when the Packers found their way out of the wilderness after 20 years of losing following Starr’s playing days, he was the revered father figure to the Hall of Fame quarterbacks, Farve and Rodgers, who eventually returned the team to greatness (though not at Starr’s level of greatness).

His last years were harsh, but punctuated by one final Starr turn, the magnificent curtain call in front of 80,000 and Farve. He looked so happy, one more time back in his element, in the place he loved, with the people who loved him, unadulterated . He drove out to meet Farve in a covered golf cart, in miserable, cold and rainy conditions, crossing the south end zone, where 48 years before he had found footing, and carried his team on his back, into history.

Greatness is not just performance beyond expectation. For Bart Starr, it was a continuous state of being oriented toward a heightened expectation of self, in what he expected of himself , what he was willing draw from others, and what he expected to give to others. He is one of the few people in this world who lived up to his myth and made those around him better for having known him. In a world where celebrity often leaves no trace of contribution, this was one shooting star who left a brilliant effervescent path through the heavens. As he likely is now doing, with his characteristic perfect execution …