At the turn of the twentieth century, hundreds of years of tonal expression and its link to cultural identity were about to be swept away by a musical revolution tied to global modernity. Rejection of classical music structure seemed to mirror the rapid industrialization and seeming contracture of the tribal world into a globalized modernism with a new universal language, atonality. Music, that for centuries had been predicated on tonal roots and associated chords resulting in music that was constrained in keys, suddenly was lifted from these constraints, and with it, the need to relate directly to the listener. The associated related rules of musical theory and counterpoint quickly surrendered to new freedoms and the shock to audiences was total. First inklings of a new reality with Debussy and particularly Stravinsky left the listening audience confused and unsettled. World War I in all its horror finally separated music from its humanistic core and composers like Berg, Schoenberg, Messiaen, and Webern left tonality for good. Music now had a harsh and raw core that no longer asked the listener to be moved or elevated, or an emotional participant. Such “emotion” tempered music found its way out of “serious” music, and into music halls, broadway theaters, and the new invention of recorded sound. Serious music was no longer about the width and breadth of human emotion.

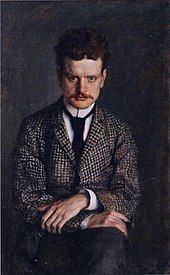

One particular great composer found it hard to leave behind the bond between humanity and nature. Jean Sibelius had musical heroes that were of a time past, and was forever connected to the epic nature and sweep of his Finnish homeland. Born in 1865, he attained musical adulthood in a musical universe that was in the last vestiges and, at times over reach, of composers such as Brahms and Wagner, and later, Bruckner, Mahler, and Tchaikovsky.

He grew up hoping to be a great concert violinist, and eventually became a passable one, but his real genius was soon to be recognized in composing for the reigning king of musical expression, the orchestra. Sibelius was from the obscure corner of western civilization, the Duchy of Finland. Caught for centuries between overpowering neighbors of Sweden, Germany, and Russia, the turn of the twentieth century began the stirrings of a unique Finnish identity. Sibelius, who grew up loving the magnificent rural vistas of his homeland, was stirred to compositional greatness with his tone poem, Finlandia, and with it renown far beyond his home country.

Finlandia achieved what great patriotic pieces could achieve, a stirring of pride in people with little or no connection to Finland and its yearnings. Sibelius did not sound quant and folk shaded, like his Norwegian contemporary, Grieg. Sibelius revealed a Beethoven like virtuosity with orchestral timbre, particularly his recognition of the primordial pull brass has on the human psyche. What does nature beyond its sounds, sound like? What emotion is revealed in the juxtaposition of frozen air, grand lake vistas, and endless forests? To be one with nature was not a lonely sensation, but rather a sacred one, and Sibelius could paint as well as any, the unspoken bond between an individual and the world they knew best. This was not the gentle beauty of a pastoral scene, this was God’s Creation, and everyone who heard it was stirred. Including the Russian Czar, who was not interested in any separation from the empire of his Finnish subjects, a psychological battle that became a bitterly physical one in World War II. But Finlandia was but a morsel compared to the scope Sibelius achieved with his Second Symphony. The tension, emotion, scope, and glory achieved by Beethoven, so elevated in the 9th Symphony, was for every composer to follow, confronting the risk of creating a pale imitation – a mortifying notion. The young Finnish composer went directly at the titanic structure of Beethoven with the 2nd Symphony, and triumphed. No twentieth century symphony is held in greater esteem by audiences, who are in turns meditative, distraught, fearful, heroic, and ultimately epically triumphant by Sibelius’ brilliant orchestration. The Finale, whose coda reaches the epic sound of a celestial organ, can frankly bring tears associated with the sense that one has triumphed over death and has been shown a glimpse of salvation and eternity.

Sibelius would know many triumphs including his Violin Concerto, 5th Symphony, and Valse Triste, among many pieces in constant rotation today. The prodigious works suddenly came to a sudden halt in 1926, and for reasons still unclear, Sibelius’s compositional muse fell silent. The last thirty years of his life were essentially barren for further extensive works, though he continued to experience acclaim for his earlier creations. Was it the move away from the world of music Sibelius loved, into a dystopian sound he had no fealty towards? Was it the collapse of the world back into darkness with the second world war exploding further the myth of a shared humanity? Sibelius himself left no direct explanation, but it was evident in his self destruction of his own unfinished works at the end of 1945, that he had no intention of being a shadow of himself, or an uncommitted contributor to the new world musical order.

Sibelius did leave us with a full palate of masterpieces that have stood the test of time, and tower over the more dystrophic musical contributors of the twentieth century. As much as the academic world has attempted to wrest the concept of music away from the appreciation of the listener and be self indulgent in the mathematical paradigms of modern atonality for the joy of the performer only, the works of Sibelius resonate with each and everyone of us. We may not have seen nature with the acute eye that Sibelius saw it. We may not understand all the nuances of tidal emotions and rhythms he sought to evoke. But in our gut, we know of the Glory Sibelius knew, and are glad for the chance to have it well up within us, and to have his creations, reveal our own.

“Sibelius revealed a Beethoven like virtuosity with orchestral timbre, particularly his recognition of the primordial pull brass has on the human psyche.” No coincidence that God announces the revelation of His Kingdom on earth trumpets and not guitars. : )

Exquisitely said… thank you!