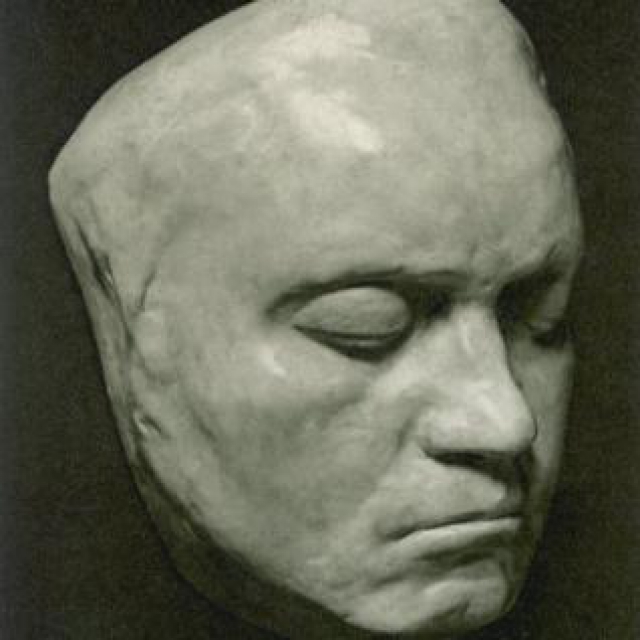

Ludwig Von Beethoven died in 1827, likely not hearing reflected in performance a single note of his composed music in the last 13 or so years of his life. An all occlusive deafness stole any semblance other than vibration of the complex sound paintings he was continuing to create, with nothing but his memory of sound and prodigious compositional talent to guide him in his later years. Yet, this profound silence proved no obstacle to an other worldly genius. Beethoven’s life mask as seen above, created in these difficult years, emotes a deep internal projection that is unmistakable. This is a man who lives among the profoundest of thoughts in his soundless prison. Beethoven wanted in the time he had left to attempt to leave for the world a record of his vision of a passionate life, and the conquering of death. He left us his entire conceptualization in the experience that is the Ninth Symphony.

I have been around classical music my entire life, but I honestly have not been ready to absorb Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as a profound personal experience until now. This specific symphony has been used and misused to adorn everything from unique shared human events like the tearing down of the Berlin Wall and reunification of the German people to commercials and phone ring tones. Most who have stated they have heard it, have heard only snippets, and would be overwhelmed and subsumed by its immense size and scope. Easily twice as long as any other Beethoven Symphony, it clings fragilely to faint outlines of symphonic structure while traveling in directions never previously conceived, and demanding a commitment from the listener few other musical creations ask. Each of the four movements stand nearly as a complete symphony, with drifting lines of intensity, sudden rhythmic shifts, sublime beauty, and echoes that later would be referred to as motifs. It is exhausting for performers, singers, conductors, and the audience as Beethoven peals back raw layers of emotion, than expounds upon them, never to finish them, demanding ever more commitment to see the piece as a whole . It is the complete cantata of a man’s struggle with his mortality and the conceptualization of the yearning for connection with the eternal. Beethoven, initially composing this never before heard musical experience, may not have originally conceptualized a choral ending movement, but the finished product recognizes his recognition that only the human voice raised to heavenly sound could provide a final enrapturement. Thus the unforgettable finale of the choral last movement.

My father passed last year, and I believe his struggles in his final year prepared me finally for the whole of this great work. I prepared myself with study for a scheduled performance, and finally heard it last night in its entirety in live performance , performed by the Milwaukee Symphony and Chorus. I was transfixed. In the end, transcendent, and with most in the audience, emotionally tearing. Beethoven, in triumphing over his deafness, has left us with an inkling of the eternal.

The first movement sets the tension with an opening like no other previous work. A sustained chord layer is built like a slowly wakening consciousness until it uncoils into an intense rage, partial melodic infusions work around the orchestra in an unhurried Allegro pace. An attempted more pleasant second theme is wrenched back into the tense minor chord of the first theme, refusing to let go. This is a dark and troubled place Beethoven’s mind is inhabiting, asking for some clarity to the strife and pain life brings, particularly in an age when a person’s many ailments had to simply be suffered, for no treatment was available. The music of this first movement introduces us to dissonance and makes us uncomfortable. It elicits a sense of heroism but denies an ultimate triumph.

The second movement in typically symphonic form would normally allow respite from the tension of the first movement in both tone and length. Beethoven would have none it, inserting an even more agitated scherzo, in place of a typical quiet idyll, then expanding and evolving it to previously unheard of complexity and length. When the second theme is introduced as a buoyant trio to restore hope and a veneer of control, Beethoven creates a tug of war between the two themes and refuses to relieve the angst.

We have now pulled ourselves emotionally through over 40 minutes of music and are not yet half done. Beethoven thus far denies us even a hint of the redemption for a difficult life.

And then, exhausted, we are lifted to the stars.

The third movement takes the unexpected pace of an Adagio, and slowly elevates us to the metaphysical. Beethoven was a great composer in many idioms , but he and Mozart were absolute geniuses when it came to Adagio slow movements. We feel slowly freed of our earthly responsibilities and tragedies and long for the beyond, mysterious and as of yet unresolved. Then towards the end of the Adagio, trumpets suddenly interrupt our idyll to signal a dramatic awareness, the orchestra tries linger, the trumpets return more profoundly and the orchestra exclaims the famous Glorious Chord. We look up to see what is to come…but it is not to be, and the movement ends with an unresolved yearning. Has Beethoven taken us this far, only to tell us there is no meaning, no resolution to this life?

The fourth movement then goes where no symphony had ever gone before. Each of the three previous movements’ motifs present, only to be rejected each time by defiant cellos and basses, that interrupt and refuse to be pulled down into any of the preceding tension and indecision. No – there is a way out and a way up, and the deep sonorous voice of the orchestra, the cellos, basses and bassoons quietly begin to declare the theme of triumph we now recognize as the Ode to Joy. Beethoven finished the symphony in 1824, racked by deafness and disease, sufficiently ill that he would die only three years later. He wanted the world to know that his soul, our soul was not bound by our earthly limitations, but would ultimately be transcendent. What follows is 25 minutes of the messiest glory filled music in the history of composition. The Frederich Schiller’s poem Ode to Joy declares a singular humanity and connection to a Supreme Being beyond the celestial heavens — and Beethoven describes this transcendent joy in a magnificent heavenly cacophony between singer soloist, choir, and orchestra inhaling and exhaling like a supernatural bellows, seeking higher ever higher ecstasy until culminating again in an even more Glorious Chord of all three. Then again, the silence…is it over? No…. No, a quant little “turkish” march breaks out , and the process begins all over, march becomes fugue, fugue becomes a brilliant full orchestra presto, and then again quiet. We seek one more time to imagine a salvation. Schiller’s line -“Brothers, above the starry canopy, there must dwell a loving father” rings out in hymnal form by the choir, and then all heck breaks lose as the answer is a resounding yes, first led by the soloists then, maximally surging choir and orchestra, until like a massive celestial pipe organ, the immense colors and sound drive an explosion like the crescendoing path through a comet’s tail, into an indescribably joyful resolution that leaves the performers and listener utterly exhausted, and profoundly transcendent.

There can be no experience that rivals unadulterated emotion. Beethoven changed the musical experience forever with the ninth and changed the perception and standard of excellence of every composer that followed him. The outright intimidation of the genius of Beethoven’s epic masterpiece left many unwilling to create their own Magnum Opus for fear it would pale in comparison to the Olympian Ninth. It has become the musical expression of what we ideally wish to project as our common humanity and best impulses. Called to greatness, Beethoven triumphed. If you get a chance someday, to experience this first hand, as I did, be prepared to be shaken to your core. Until then, watch one of the greater performances preserved for all time, in Sir George Solti’s London Philharmonic performance in 1986. If you can find the time try to master the performance as a whole and live the complete transformation — if you are strapped for time, immerse yourself in the final movement begun precisely at the one hour mark ( 1:00:00) and the glory will still envelop you…

There’s been quite a lot written about the tempo at which Beethoven should be played and NPR’s Radiolab had a program devoted to this also. Will give the Ninth Symphony another listen!

BEAUTIFUL