John Everett Millais

1851-2

In a large rectangular room in the Tate Britain Museum, a modestly sized painting draws the eye among all others. A beautiful young woman floats in a stream surrounded by a dense, fecund growth, drifting silently down a quiet stream, surrounded by flowers of florid color and variety. But this is not a scene of serenity. A pall lights her features, her eyes see nothing but madness and impending death. Her hands are held in a pose of complete surrender, grasping but not feeling a bouquet of violets, nettles and daisies, which cascade into a floating pool of withered stems on her shimmering waterlogged gown. She is Ophelia, Hamlet’s scorned love, driven to madness and suicide by the dark Prince of Denmark. And Ophelia is the signature painting of John Everett Millais, that announced the arrival of a brotherhood of British artists known as the Pre-Raphaelites, heralding a full blown romantic movement in 19th century art.

In 1848, a group of young artists determined to shake the art world through a conviction that art had become statuary, overblown, and disconnected from the natural aesthetic of the world of creation. The group of seven – John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Rossetti, William Holman Hunt, Frederick Stephens, Thomas Woolner, and James Collinson – declared their disdain for the accumulated artifice of contemporary art, and harkened back to a time prior to the revolution of art propelled by Raphael and his acolytes. For inspiration, they left the subject matter of fawning portraiture of royalty and idolatry, and defined a list they referred to as the “Immortals,” a disparate list of historical figures such as Jesus and King Arthur, diverse literary scions such as Shakespeare, Browning, Poe and Shelley. They set four basic rules for the Brotherhood of the Pre-Raphaelite. 1) To have genuine ideas to express 2) To study Nature attentively, so as to know how to express them 3) To hold sympathy with what was direct, serious and heartfelt in art prior to the Raphaelite school and, most importantly, 4) produce throughly good and beautiful paintings and statues. The sentinel evocation was Millais’ masterpiece of Ophelia, and the art world was stunned and even disturbed with what they saw. Prior romanticism was held privately between the pages of a book. Ophelia pulled the viewer into a world of intense feelings of pathos, pity, the world of mental derangement, and an intimate voyeurism that left many uncomfortable. In the age of Victoria, the public acknowledgement of baser human feelings and passions were not a socially acceptable norm. The popularity of what propelled from the seven artists suggests however, that the contemporary norms veiled a simmering intensity that had found a vehicle for expression.

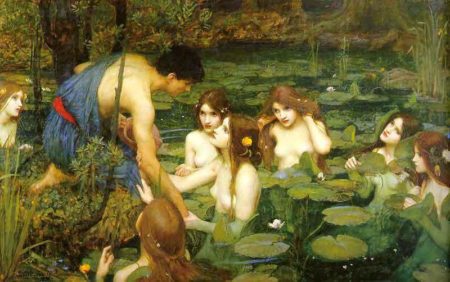

The pre-Raphaelites formally cooperated only until 1854, then broke apart into various art directions. The intense romanticism of the paintings inspired a whole school of art and literature focused on the simple aesthetic of beauty as found in both human form and nature. In literature, the Aesthetic Movement emulated the artistic strokes through writers such as Oscar Wilde and stylized through physical crafts such as furniture and pottery, the so called “art for art’s sake” of the Arts and Crafts Movement. The painters Rossetti and Waterhouse expanded the art form into overarching portraiture of idealized human beauty that bordered on sensual in a time of contracted public emotional expressions. John William Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs extends the flower symbolism into the realm of the human sensual, with the pure water lily painted along side nymphs that symmetrically reflect the lily’s youthful beauty and purity,. They are colorized by the artist as a reflection of the lily in human form, peerlessly white skin, languid lines, but with a hint of danger as they, like the lily, float above a dark murk and intend a dangerous attraction for Hylas, who is mesmerized by their ethereal beauty. The flower allegory pulls the intense power of nature and its primordial instincts through the painting that prevent it from becoming a vehicle that could suggest leering without the balance.

John William Waterhouse

The focus on beauty as an artistic expression pushed into the twentieth century but became mired in excess and repetition that left the world ready for the bound away from realism through the light show of Impressionism and inevitably the distortion and evocativeness of the genius that was Picasso. Beauty, like flowers in bloom , appropriately is transient and comes against the harsh realities of life. Shakespeare’s masterpiece Hamlet, presented an anti-hero to the world and evoked the pitiful fragility of beauty and innocence through the brief but unstable vision of Ophelia. John Everett Millais achieved the core of Shakespeare’s expression through his alliteration on canvas of Ophelia in a stirringly poetic and faithful representation of the tragedy of Ophelia, so masterfully evoked by Shakespeare through Queen Gertrude’s beautiful eulogistic soliloquy:

There is a willow that grows askant the brook, that shows his (hoar) leaves in the glassy stream. There with fantastic garlands did she make Of crowflowers, nettles, daisies, and long purples, That liberal shepards call a grosser name, but our maids do “dead man fingers” call them. There on the pendant boughs her coronet weeds Clam’ring to hang, an envious silver broke, When down her weedy trophies and herself fell in the sleeping brook. Her clothes spread wide, and mermaid like awhile they bore her up, which time she chanted snatches of old lauds, as on incapable of her own distress. Or like a creature native and endued unto that element. But long it could not be till that her garments, heavy with their drink, pulled the poor wretch from her melodious lay To muddy death.

There is a willow that grows askant the brook, that shows his leaves in the glassy stream. There with fantastic garlands did she make. John Everett Millais captured the moment for us all to glory in, the majesty and beauty of life, so fragile and so capable of madness and sorrow that comprise humanity.

One can see Ophelia and the many other masterpieces of the Pre-Raphaelites at the Tate Britain Museum.