Two coiled springs had been tightening, gaining immense potential energy for years. The question was simply where and when the spring would release, and whether it would be premeditated, or spontaneously let go. The overwhelmingly powerful British Empire, supported by the greatest military capacity present anywhere, was coiling against a perceived challenge to its authority that had consequences that were simply unacceptable for its very being. The opposite spring, a group of British subjects in the far away American colonies, saw a world that had yet to be invented, and like a prophet that had foreseen the glories of heaven, could not wait any longer to undertake the ascension. On April 19th, 1775, the spring uncoiled, and the whirlwind was released.

Since the climax of the French and Indian War, that in 1763 left Great Britain in the dominant position on the North American continent, the seeds for strife between the British crown and its colonial subjects grew progressively, and inexorably. This journey to the American Revolutionary conflict is (or at least was) an essential foundation of every elementary history course. Following the French and Indian war, the British Parliament felt that a significant burden of the massive financial debt created by the war should be assumed by the American colonies given the tremendous advantages for growth and security that had been created for them with the victory. The most direct was the Stamp Act, a tax that the colonists objected to not so much that it was oppressive in size, but rather in that it had been enacted without any representation and discourse with the colonies. With the elite educated class in America, progressively enthralled with the momentum of what would be called the Enlightenment, the lack of ability to influence their present or future was intolerable to the concepts of personal liberty and freedom of initiative.

Particularly in the restive New England colonies, radical discussions and progressively organized dissent proliferated. One such group, the Sons of Liberty led by Samuel Adams, became recognized as driving for a world beyond British parliamentary representation. The Adams radicals looked to kindle the fire that would make the world anew. The answer from Great Britain was to assert its authority, and progressively British regular soldiers were seen in Boston. The spark first showed itself in the so called Boston Massacre of 1770, in which a platoon of British soldiers threatened by a snowball throwing mob lost its cool and shot into the crowd, killing three. The Boston Tea Party of 1773 led by Samuel Adams was a direct affront, and the British government saw a local problem beginning to spiral out of control. The response that turned the process into an irreconcilable mess were the Intolerable Acts of 1774 enacted by Parliament, that asserted a form of military dictatorship over the colonists, restricting assembly, seizing control of the critical Port of Boston, removing a legal authority over British troops by American courts, and allowing British troops to be housed in American homes without consent of the owner. The response was predictable, for now the colonists that for 150 years had pretty much determined their own way in the Americas were forcibly notified of their subservient position in the British hierarchy. The colony of Massachusetts exploded in fury, and initiated a shadow government to the local British authority, a Provincial Congress that put forth the Suffolk Resolves, a group of acts that declared a boycott of British goods and public disobedience with the Intolerable Acts until they were repealed. Even more worrisome and threatening to the British, a meeting of all American Colonies took place in September 1774, forming a continent wide shadow legislature known as the 1st Continental Congress, that suggested the local radicals had permeated the concept of disobedience to British authority across the entire continent.

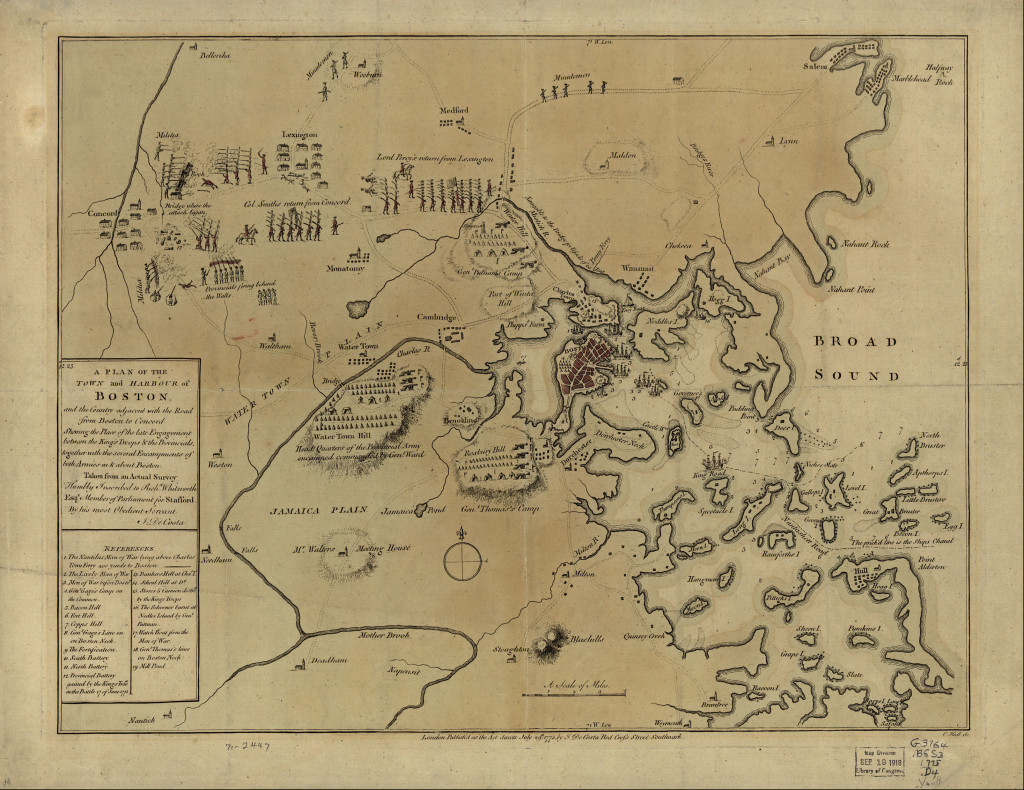

The Suffolk Resolves suggested the detachment of British authority from its American colonies and was an Intolerable Act to the conservative parliament and the king. Regular army detachments were sent to Boston to put it in a vise, and the reaction of the colonists were to form organized militia capable of rapid deployment with arms collected and positioned for maximum impact in case of conflict. The arms were distributed to allow 12000 militia to respond immediately to an aggressive British military maneuver, secured in 50 man units known as Minutemen. The commanding general in Boston, General Gage, recognized he could not possibly stand by and allow an organized force to arm itself. He determined to extend his forces into the countryside with strength, arrest the radical leaders, break up the militias, secure the arms, and send the leaders back to Britain for trial for high treason.

The when was April 19th, 1775 and the where was the public green in Lexington and the Old North Bridge in Concord.

Gage heard of massive stores of arms being collected in Concord, Massachusetts and selected the little town 24 miles from downtown Boston to be the sight to reassert British authority. The goal was to send overwhelming force in a stealthy fashion, marching through the night, but Boston was rife with spies, and the rebels had already planned for an early warning system. When it was determined that British troops were moving and their determined target, the Internet of the time sprang into action. Horsemen, most notably the silversmith Paul Revere, left Boston in three directions to alert the many communities that contained the Minutemen companies, and for the most part succeeded in marshaling the rapid deployment force before the British could intercede. Gage sent a massive force of 700 regulars on the road to Concord, with a desire to break arm stores in the intervening towns of Monatomy and Lexington.

At Lexington green, just as the sun came up, the advance British forces encountered the first of Revere’s alerted Minutemen led by a grizzled Indian fighter named John Parker. 77 minutemen stood in formation on the green nervously facing a representation of the most powerful military on earth, led by Major Pitcairn of the Royal Marines, who demanded the “rebels” immediately disarm and disperse. Parker, fully aware of the gravity of the moment and the importance of how it had to evolve to secure the right side of history, had told his men earlier, “Stand your ground. Don’t fire unless fired upon. But if they want to have a war, let it begin here.” There appeared to be a brief moment of indecision as both sides realized what might result from a mistake, but a shot rang out, and the British fired a point blank volley into the Americans. The damage was done. 8 Americans lay dead or dying and the British moved in and bayonetted. The minutemen dispersed and retreated to Concord. The British marched on to Concord and soon realized they were in a world of trouble. Initially the town allowed them to search uninhibited, but it was obvious that the weapons stores had already been removed, and the British became frustrated and burned downed several structures in town. British detachments moved to secure the bridges into town, and at the Old North Bridge it became clear the honeybees were being replaced by hornets. Minutemen were waiting for them on the bridge, and this time they didn’t just accepted the punishment delivered at Lexington. The volley was returned, and this time there were dead on both sides. As Ralph Waldo Emerson famously described,

By the rude bridge that arched the flood

Their flag to freedom’s breeze unfurled

Here once the embattled farmers stood

And fired the shot heard’round the world

The British retreated, and it became apparent that a potential calamity was underway. The officers began to retreat back toward the safety of Boston, and the extent of the hornet’s nest they had kicked over became apparent. The march back to Boston became a Hell’s road, facing a fully aroused guerrilla force, having been made aware of the morning’s events and sacrifices, that sought nothing short of full annihilation of the 700. Behind every rock and tree for twenty miles, a diffuse force of militia trained in the savage warfare of the Indian conflicts, snippered, ambushed, and harassed the beleaguered British force to massive loss, saved only by a rescue force from Boston that brought heavy artillery and cavalry to bear. The proud British force had been decimated with 0ver 250 casualties compared to 88 for the American militia, and came within an eye-blink of complete annihilation. The British, who hoped to assert complete authority, now found themselves under siege in Boston ringed by an entire countryside of furious hostility.

There was no going back from the brink, and the whirlwind was unleashed. The fighting was more savage than anyone could have predicted, and the losses stunning to the British. The Americans recognized the next battles would be of epically greater scale and began to form a Continental Army led by a Virginian named George Washington. The British saw that this was no longer a mob action led by a small minority, but a growing fire that could consume their hard won dominance in North America.

It would take 8 years of incredible sacrifice, amazing moments of heroism and initiative, epic mistakes, and a level of savagery of relative against relative that would presage the Civil War 80 years later. At the end of it all stood a dream and a promise, of equality of men, freedom of thought, and liberty in action that is as close to anything that man can claim as inspired greatness. On the 241st anniversary of the April events that shook the world at its foundations, we can only gaze in awe of the tiny contingent of brave men who stood their ground in a little town in Massachusetts and were willing to make such an ultimate sacrifice, on the sliver of faith that a promise could support a dream and create a better world. The impossible was made the possible, and the possible, happened. The dream and the promise held by common men were able to surmount the greatest military force of their time and turn the world upside down. Some felt it was Divine providence; it amazed even the most secular of men, when they looked back and realized what had transpired. As fellow Virginian John Page wrote to Thomas Jefferson after the after the Declaration of Independence was signed:

We know the race is not to the swift nor the battle to the strong. Do you not think an angel rides in the whirlwind and directs this storm?

We are still in the whirlwind of history. Maybe we will once again listen to our better angels, and find our way through our current storm.