At the western edge of the island land masses that form the Hebrides off the coast of Scotland, stands a little tuft of volcanic elevation known as Staffa. Barely a quarter mile in area, the southern most tip of this uninhabited island faces the huge expanse of the Atlantic with a peculiar formation of crevice, cave, and stone referred to as Fingals Cave. Despite its natural isolation, it has been reknowned for as long as there has been humanity on the islands known as Albion for the strange cathedral like natural formation of its prismatic hexagonal basalt columns formed by the slow cooling masses of sea lava that pushed out of the sea and were reoriented by intermittent flooding of the lava flows by the great ocean. Natural formations such as Fingals Cave have taken on supernatural characteristics to those who are open to its coalescence of sights and sounds that seem to have been directed by an unseen hand into something beyond the sum of its parts. At a certain time of day, in a certain light, the very rational explanation of the natural formation in the shadows and mists is progressively lost to the mysterious otherworldly sensual experience of that which is beyond explanation.

It is in that place, that an entire cultural line of creative thought we now refer to as the Romantic Age propelled out of the rationality of the Enlightenment of the seventeenth century. Enlightenment, with man as rational thinker, and God as Engineer, saw the world as ordered and explainable, limited only by the means available to understand it. At the turn of the 18th century and for fifty years following, a reaction to this ordered universe developed in the cultural world that connected the internal world of unspoken thoughts and dreams to the great unknown of the supernatural, and sought expressions in their writing, art, and music. The writings of Shelley, Wordsworth, Lord Byron, Robert Burns and William Blake, the paintings of Goya and Friedrich, and the music of Mendelssohn and Schumann, Liszt, Chopin, and Berlioz provided a reaction and withdrawal from the very real turmoil of the marshal and nationalist Romanticist impulses optimized by the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.

Though a multicultural movement seen in every western society of the time, the greatest amount of definition came from the german remnant of the Holy Roman Empire, through its philosophers Harmann, Goethe and Schiller. The German expression of “Sturm and Drang”, literally Storm and Drive, referred to sublimation of the rationalist to the internal turmoil of both individualism and emotion. The natural world took on progressive attraction and awe, as it tended to stimulate unique emotions, and provided escape from the brutal realities of the development of state militaries and the darker effects upon people of the mass scale of the Industrial Revolution.

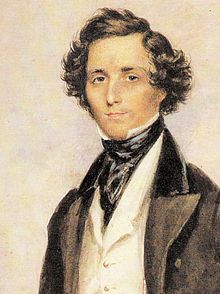

Felix Mendelssohn is the somewhat under-appreciated musical master of his time. Typical for his age, he accomplished a prodigious amount in the very short life span so common before the Age of Medicine. Born in 1809 in Hamburg of a prominent intellectual Jewish family, he suffered under the rigid anti-semitism of european culture.Raised in a secular home, he was eventually converted to Christianity, but insufficiently Christian for most of european society, and insufficiently Jewish for his own understanding of his people and ancestry. Although his family with its Christian conversion took the name Bartholdy, Mendelssohn never fully dropped his ancestral name, and his courageous juxtaposition defined his relationships for the rest of his life. This inner turmoil provided an exceptional platform for Harmann’s Sturm and Drang, and the undeniable genius that was Mendelssohn proved a fortress of this movement’s expression over his short 38 years on earth. From the 17th century’s end to the atomic age, genius was the province of birth, not formed through scholastic preparation. This particular form of genius was celebrated for its polyglot capabilities in language, music, and art, and Mendelssohn was from childhood recognized for the depth of his intellect and the prodigy level of his talents. Like Mozart, he was born a musical prodigy, by age 17 already considered at the highest order of pianist performers and composers, completing his seminal overture to the Midsummer Night’s Dream by age 16, and the aforementioned ode to Fingals Cave by 21. The Symphonies poured out in his twenties and the great Violin Concerto in E Minor by age 33. The music was sonic, pictorial, and nativist, connecting to the internal but never losing its relationship with the classical roots from which it sprung.

It was Mendelssohn’s unwillingness to sever his connections with the ancestry of musical expression the offended the more radical romantic dreamers like Liszt and Berlioz, and Mendelssohn’s pride in his jewish roots that even more offended the german racialist Wagner, who worked to demean Mendelssohn’s reputation where he could. Mendelssohn created a very personal dream world that celebrated nature and individual but painted with a cool light that seemed too rational for the more disordered and exhibitionist world that a performer like Liszt inhabited. Mendelssohn’ s universe foreshadowed more than later cool impressionism of Debussy and Matisse than the dense emotionalism of Mahler and Van Gogh. Mendelssohn also was selfless in almost single handedly bringing back to light the genius that was Johann Sebastian Bach, almost completely buried in the past, as well as the more present works of Schubert and Schumann to prominence. It was Wagner’s racialist hatred, perhaps additionally fueled by Mendelssohn’s apparent earlier indifference to the youthful Wagner’s composing efforts, that nearly buried Mendelssohn’s musical memory. In Nazi Germany, Mendelssohn’s works were banned as reactionary and his influence scrubbed, but the universal connection felt by his audience and particularly the performers who admired the seamless perfection that was his Violin Concerto would not let his musical expression die. To the horror of the racialists, Mendelssohn’s very germaness overwhelmed their ignorant theories, and his sublime work combined with his rescue of former German cultural greatness makes him one of the titans of Germany’s significant cultural gift to humanity.

In today’s world, where our current homage is to the twin temples of Settled Science and Athletics, it is nice to harken back to the creative geniuses that saw pleasure and awe in the unsettled and mysterious nature of life, and celebrated its obtuse and otherworldly side. We don’t have to travel to Staffa and linger in the cathedral like cove that is Fingals Cave to feel our connection with the grandeur that is God’s Creation and our soul’s connection to it. We only need to close our eyes and let a genius from another age take us there and make us one with it.