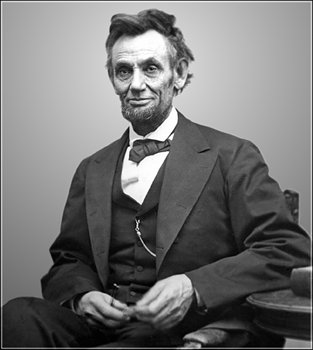

November 19th was the 147th anniversary of the Gettysburg address, Abraham Lincoln’s masterpiece of perfectly structured prose defining for all time the standard of speech writing and public rhetoric. In a mere 272 words, Lincoln memorialized the heroes of the specific Gettysburg battle, the larger principles that would be worth such horrid sacrifice, and the greater good that the cataclysmic struggle would bring to fruition. Most importantly, he re-framed and confirmed the basic argument for the existence of the American republic itself, and from that point on it was never again an subject for rational question.

Reading the words and acknowledging his exalted place in the pantheon of American history, we can easily forget this man had only a few weeks total of formal education, was fundamentally self taught, and formed almost all his philosophy from his narrow exposure to Cicero, the Bible and Shakespeare. The depth of his intellect in the face of such a hard scabble upbringing and limited means and exposure to intellectual critical analysis remind us to look again at our absurdly silly modern biases that the only intellectual leaders are those who have advanced degrees from ivy league type educational citadels.  Lincoln formed his genius the most credible way, though constant introspection, mental exercise through memorization, and intense study of the science of debate. In Lincoln’s time, the availability of significant data to prove debating points was available to almost no one, and the audience was almost assumed to be predominately illiterate. The equally important point, however, was that Lincoln had honed his debating skills in the prairie wilderness of Illinois where the powers of thought and argument, and confidence in human intuition were required to be at a highly developed state due to the necessity of surviving in such a difficult and primitive world. In the harsh loneliness of the great west there was time only for hard work and hard thought, and no one made the prejudicial mistake to assume that intellect and talent were exclusive to the schooled. Lincoln was a debater his whole life, from the skills learned as a self taught travelling lawyer on the circuit courts of the rural midwest, to the state legislature, U.S. Congress, brilliant public debates with Stephen Douglas for Senate, and finally Presidency at the moment of greatest philosophical crisis in the history of the country. He never made the modern political mistake of “dumbing down” the depth and seriousness of the argument to his audience. He always assumed the native intellect of those he was communicating to, and the need to persuade, not to indulge. In modern times, only Franklin Roosevelt, John Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan come remotely close to this innate skill set of Lincoln’s.

Lincoln formed his genius the most credible way, though constant introspection, mental exercise through memorization, and intense study of the science of debate. In Lincoln’s time, the availability of significant data to prove debating points was available to almost no one, and the audience was almost assumed to be predominately illiterate. The equally important point, however, was that Lincoln had honed his debating skills in the prairie wilderness of Illinois where the powers of thought and argument, and confidence in human intuition were required to be at a highly developed state due to the necessity of surviving in such a difficult and primitive world. In the harsh loneliness of the great west there was time only for hard work and hard thought, and no one made the prejudicial mistake to assume that intellect and talent were exclusive to the schooled. Lincoln was a debater his whole life, from the skills learned as a self taught travelling lawyer on the circuit courts of the rural midwest, to the state legislature, U.S. Congress, brilliant public debates with Stephen Douglas for Senate, and finally Presidency at the moment of greatest philosophical crisis in the history of the country. He never made the modern political mistake of “dumbing down” the depth and seriousness of the argument to his audience. He always assumed the native intellect of those he was communicating to, and the need to persuade, not to indulge. In modern times, only Franklin Roosevelt, John Kennedy, and Ronald Reagan come remotely close to this innate skill set of Lincoln’s.

The Gettysburg Address as legend has it was framed by Lincoln on the train to the national cemetery commemoration at Gettysburg, and was considered an afterthought following intense oration of Everett Edwards, the professional orator who preceded him with an erudite 2 hours of rhetoric. Ironically, it was only Edwards initially who recognized that Lincoln had done more to perfectly frame the moment in his three minutes then Edwards had in his two hours, and told him so. We can only imagine the disappointment of the crowd gathered, when the president followed Edward’s loquacious sonorous testimonial with a brief high pitched simple discourse that was over almost before it started. It rapidly however was appreciated for its perfect structure and brilliance and has come to be recognized as a jewel of english language rhetoric and human thought. If only our current leaders would be capable of learning Lincoln’s special insight into humanity and the American Experience.

The Gettysburg Address

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom— and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

A. Lincoln November 19th, 1863