In 1799, a willful, brilliant Corsican named Napoleon Bonaparte who had led French troops to multiple victories under the auspices of the revolutionary government of France, managed to take advantage of the weakened and self defeating nature of France’s governmental structure and successfully undertake a coup d’etat. Rapidly outmaneuvering the other coup leaders, he had himself named First Council, and over the next five years led France to a dominant position in Europe. In 1804, the combined power of victory and superego brought his enshrinement as Emperor of France and the aggressive and grandiose nature of this brilliant and ruthless dictator held for all of the western world the spector of French world domination.

It is one of the peculiarities of history that entire historical tides pivot around singular events, and on October 21, 1805, one of the most powerful pivots ever occurred off the coast of Spain. The pivot point, as so often is the case, identifies one man as the opposing historical force, a slight of build, intense Admiral of the British fleet who in an adult life of almost constant battle had given an arm and the sight of one eye in the service of his country. The man with an ego, tactical brilliance, and battle aggression on the seas to mirror Napoleon’s on land, was Horatio Nelson.

Added to the peculiarities of history is the fact that the catastrophic loss of the American colonies and the untold wealth of the American land mass in 1783 paradoxically positioned Great Britain on an almost unimpeded arc of spectacular commercial and military success on the world stage for the next 150 years. By 1805, Great Britain had restored world wide domination of the seas and was positioned to be the solitary check to Napoleon’s plan of world domination. Napoleon had every intention of restoring French dominance of the English isles abdicated by Henry V’s 1415 victory at Agincourt, and knew the British control of the sea lanes had to be broken to achieve his aims. He drove his French naval forces to take the fight to Britain, but struggled to find the necessary equivalent leadership in his admiralty, as most of the competent and experienced naval leaders used to doing battle with England were annihilated in the fires of the French Revolutionary tribunals. The French Admiral leading the Mediterranean french fleet was Pierre-Charles Villenueve, a cautious and realistic admiral who had thus far succeeded by avoiding direct conflict with the British, but now was under great pressure to commit to battle. He did his best to conjure up a fleet superior to Nelson’s in firepower and number of ships, but recognized the inferior depth of seamanship he had available and was fearful of the battle turning on the skill sets of individual ships. This proved to be a prescient insight.

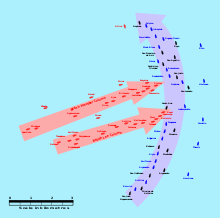

Nelson had the opposite problem. He could not get into a slugfest where his inferior numbers would be worn down, but sought instead to defy traditional tactics and try to cut the French fleet down to more palatable size. Traditional tactics called for ships to remain in line, allowing each to support the other, and keep their cannons focused broadsides on the ship they were facing. This allowed ultimate fire power delivery, and in the case of progressively poor outcome, easy ship to ship communication, coordinating either advance or retreat simultaneously. Nelson determined to trust the superior seamanship of his captains, the training of their crews, and the detailed quality of his instructions to allow his line to break and have individual ships charge the enemy line.  The risks were enormous; a ship heading headlong into an opponent’s line would for a significant period have no canons pointing at the enemy, and would be fully at the mercy of the broadside canons of the enemy ship, not a pleasant situation to contemplate for anyone on board the charging ship. Nelson gambled that the unorthodox approach if successful would get his ships in close where all the battle hardened skills of his crews would take over, and overwhelm the less experienced french and supporting spanish ships.

The risks were enormous; a ship heading headlong into an opponent’s line would for a significant period have no canons pointing at the enemy, and would be fully at the mercy of the broadside canons of the enemy ship, not a pleasant situation to contemplate for anyone on board the charging ship. Nelson gambled that the unorthodox approach if successful would get his ships in close where all the battle hardened skills of his crews would take over, and overwhelm the less experienced french and supporting spanish ships.

On October 21, 1805, off the Cape of Trafalgar, Spain, the collision occurred and history pivoted. Nelson prepared his forces with a last surge of martial pride and motivation by relaying in a special message that the success of the plan would be related to the success of each individual in the fleet to perform with courage and competence. Nelson was one of history’s unique leaders where his troops were always able to see through his vanity and appreciate his unique abilities that inevitably would increase the chances of any seaman surviving an engagement. No one doubted his personal courage, and no one doubted that in a real fight, it was always best to be tied to someone who could think in a moment of crisis. All members of that British fleet knew that was the man Nelson was in spades, and they knew he was talking in a personal way to each of them when on that fateful morning, the HMS Victory flew the semaphore flags that resonated to all in electric fashion, “England Expects That Every Man Will Do His Duty”.

It is is hard to express the violence ,viciousness, and chaos of sail driven sea battle in the 18th and 19th century to the individual sailor. He faced the horror and and fury of metal projectiles flying everywhere, both huge cannonballs and grape sized razor edged shrapnel, lethal splinters of wood, heaving seas and bloody decks making mobility almost impossible, the deafening roar of 30 cannon spontaneously firing heaving the ship and making communication imperceptable. It required a steely constitution, expert training, and years of experience for every man to “do his duty” under such circumstances.  Through it all, the tradition of leadership required the captain admiral to be imperious to it all, in full view of all his men and the enemy, to provide the ultimate “backbone” to the effort. Nelson knew in his heart that ultimate victory would likely on this day would require ultimate personal sacrifice, and resisted all efforts to reduce his exposure to enemy fire. In the heat of the charge, Nelson stood as men around him were cut in two by fusillade, and simply directed his ship to closer contact. With the HMS Victory in deck to deck contact with the french Redoubtable, a sniper from the Redoubtable found Nelson and struck him mortally from fifty feet, through his lung and crushing his spine. Nelson was taken below, where three painful hours later, assured that his controversial tactics had won an overwhelming victory, died, and brought himself immortality.

Through it all, the tradition of leadership required the captain admiral to be imperious to it all, in full view of all his men and the enemy, to provide the ultimate “backbone” to the effort. Nelson knew in his heart that ultimate victory would likely on this day would require ultimate personal sacrifice, and resisted all efforts to reduce his exposure to enemy fire. In the heat of the charge, Nelson stood as men around him were cut in two by fusillade, and simply directed his ship to closer contact. With the HMS Victory in deck to deck contact with the french Redoubtable, a sniper from the Redoubtable found Nelson and struck him mortally from fifty feet, through his lung and crushing his spine. Nelson was taken below, where three painful hours later, assured that his controversial tactics had won an overwhelming victory, died, and brought himself immortality.

In a battle of forces in which he was outnumbered 32 ships to 27, 2500 canon to 2100, and thirty thousand men to 17, 000, Nelson’s forces captured or sunk 22 ships and lost none. The devastating loss was one from which the French navy was never to recover, and put on permanent hold Napoleon’s plans for invasion of Britain. Presaging Hitler’s decision following the calamitous loss of the air Battle of Britain on 1940, Napoleon averted his eyes west and turned east toward Russia, and his eventual defeat and decline, the final blow at Waterloo in 1815. Great Britain took Nelson’s victory and its now unrivaled seapower to create the largest empire the world had ever seen over the next 100 years. The historical effect, a world dominated by the English language, not French; by commercial trade and mercantilism; and the British system of education and justice.

On such days, western civilization and its concepts of individual achievement, revels.